My wife and I recently went to see “A Complete Unknown” about Bob Dylan, and it prompted a night of remembrance and reflection on my life in the mid-sixties.

Brought up in the middle-class suburbs of New York City, I enrolled at NYU’s Institute of Film and Television, and at eighteen I moved into a studio apartment on St. Marks Place. In 1967 the Vietnam war was ramping up, and getting a student deferment was part of my plan.

The building on St. Marks was a tenement, an old building in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, a Polish neighborhood that had housed poor immigrants for a century. My studio on the fourth floor had a couple of windows overlooking the street, better than the tiny studios in the back of the building with light shining down a dirty airshaft.

Raising issues about the building was useless. The Super was called “Uncle Joey” but I learned that Joe Romatowski had worked as an enforcer for the Dutch Schulz mob. Now a graying old Pole, he sat all day in his back-of-the-building studio in a sleeveless t-shirt smoking cigarettes and fantasizing about getting laid by hippie chicks. And as warm September turned to cold October, building issues did arise, like no heat.

The fourth floor was too far from the building’s ancient boiler, and hot water never made it to my radiators. Ice formed on the inside of the single-pane windows, and to warm the place up I lit the burners on the gas stove. Stupid, but it worked.

That same October, I went to Washington D.C. to join the anti-war march to levitate the Pentagon. I hitched a ride with a carnival barker who practiced his pitch for five hours. By the time we arrived, I’d learned how to make money hawking cheap pens.

The march was glorious, although it ended at the flagstone steps of the Pentagon with a crowd of us marchers surrounded by soldiers and U.S. Marshals who tormented us with canteen water and billy clubs. The Pentagon stayed put and at 10 p.m. I split.

Back in New York, my English teacher at NYU assigned us to write a 42-page paper on the poems of Dylan Thomas. He was a great poet, but my leanings were to Bob Dylan, and with my Pentagon march, the Vietnam War and all, writing a 42-page paper was out of the question. Knowing my student deferment was at risk, I nonetheless decided to withdraw from NYU.

When I informed the Dean of Students, he sympathetically said there were times he was tempted to throw his file cabinet out the window. Nice guy. I felt free, dropped out, left school, got cool, tuned in, turned thin, grew a ‘stache, and lived on twenty-five-cent cabbage pierogis.

Meanwhile, the scene in the East Village turned ugly. The Summer of Love shriveled into a Winter of Squalor: psychedelics gave way to street drugs and flower children had their arms amputated from infected abscesses. Front page news in the underground newspaper “The East Village Other,” a kid nicknamed “Groovy” died of an overdose; it was time to get out.

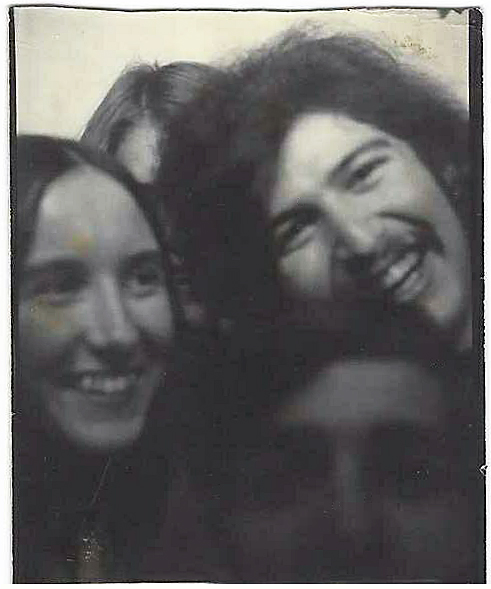

I moved in with a girl named Peggy who lived on 87th Street on the Upper West Side. We got robbed a couple of times and moved to 71st. Within a year we were on a plane to San Francisco, escapees from the squalor of New York.

Those were the days, my friend/we thought they’d never end . . .

Love learning about your early beginnings!