Are you a Stoic or an Epicurean? Maybe you’re a Cynic, or a combination of all three. However you think of yourself, it’s likely that you hew to one philosophy or another, even if you know next to nothing about any of them.

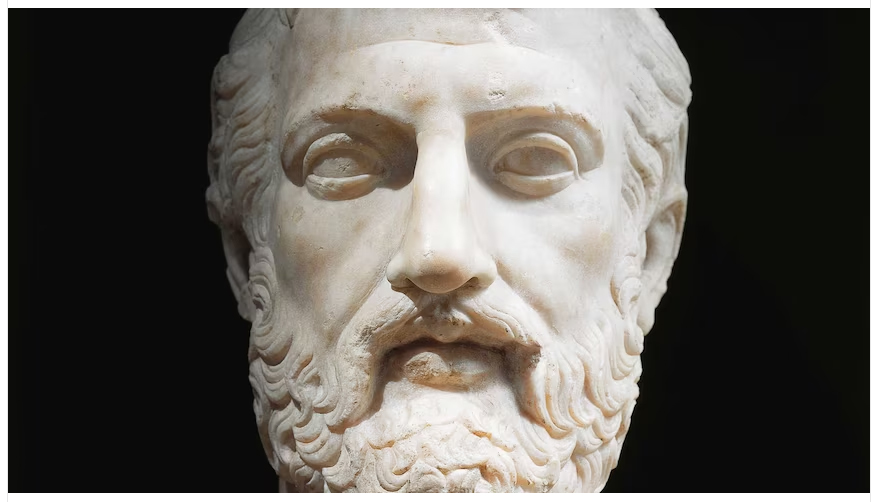

The origins of western thought are rooted in the philosophy of Ancient Greece. In the process of spreading their domain across Europe and the Mediterranean, the leaders of the Roman Empire adopted the philosophies of Greece, and well, here we are. For the Greek philosophers, it all began with the logos.

The Greek idea of the logos can’t be fit into one simple box; the logos encompasses the divine: gods, nature, and time, the irresistible force that impels the universe forward, and we along with it. Not just an idea, the logos was thought of as something material that fills the world, like air. In this way, logos is somewhat like our modern conception of God, filling and investing itself in everything.

For the Stoics (300 B.C.), this led to a deterministic philosophy tied tightly to cause and effect; if the logos permeates everything, dictating the course of events, then people are simply carrying out what’s been laid out for them in an unknowable but nonetheless fully structured universe. Our modern conception of it is God’s Will. In the face of being at the mercy of irrevocable causes and effects, the Stoic approach is basically to “keep a stiff upper lip” – “keep calm and carry on.” A Stoic attitude is one of action, doing what needs to be done in ethical harmony with events and custom. Accordingly, in childhood we’re advised: “row, row, row your boat, gently down the stream.”

Epicureans embraced the logos as well, but rather than seeing existence as a highly structured sequence of inalterable cause and effect, they conceived the universe as unpredictable and random, not deterministic, similar to the way in which we’ve defined the quantum realm as indeterminate. That being the case, seeking pleasure and peace while embedded in an otherwise difficult and uncomfortable existence appealed to Epicurean Greeks. In our modern times, the meaning of being an Epicurean has morphed into seeking hedonistic pleasure, particularly with food, but its philosophical roots were about quiet contemplation. Unlike the Stoics, Epicureans elevated feeling, thought and intellect over action. “Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily,” they might have sung, “life is but a dream.”

The Cynic philosophy grew out of Stoicism, favoring nature over the works of man, and seeing the logos displayed in the natural world around them. Suspicious of man-made social institutions like systems of government, Cynics rejected the action-oriented activity of Stoics as well the accumulation of material goods, preferring instead to place attention on creating a utopian life of virtue in communal concert with nature. In today’s world, being a Cynic has acquired an air of pessimism, and tends towards anarchy, conspiracy theories and even paranoia.

This summary is a great simplification, of course, but it’s none-the-less interesting to note the ways that these ancient philosophies remain visibly at work in our 21st-century psyches. Our American character embodies elements of all three philosophies, clearly manifest in our social, political, and economic spheres of life.

That philosophical ideas over 2,500 years old remain so operative and instrumental in modern society speaks to something archetypal about us. While cultures may change and societies may evolve, what makes us human stays pretty much the same.