“It says here that seniors are changing their spending habits due to inflation,” my wife mentioned to me yesterday, “eating out less, just like us,” she added. “Yup,” I replied, “we’re just a statistic.”

For many years I’ve said, “I’m just a statistic,” a comment that’s often irritated my wife, but as a child of the Boomer generation, while I watched The Adventures of Superman on black and white television, tens-of-millions of us were watching. While I wore bell bottomed pants as a teen, all my friends did; now as a senior, we all take Lipitor and wear compression socks. Whatever my unique features as an individual have been and still are, at another level I simply embody and manifest the ailments and habits of my peers.

Was it possible to see all this coming, the technology, the social trends and mass conformity? Not entirely. Like observing the wave-like behavior of quantum particles, it’s impossible to know the outcomes of the specific trajectory of human lives with certainty. Humanity is not subject to the predictory calculus of Isaac Newton that lets us successfully shoot a rocket into an asteroid at the far reaches of space; the complexity of chance and necessity make that impossible. The present moment represents the sum of all past actions in an inconceivably complex universe The best we can do is assign probabilities to the future, or if we prefer, generate statistics.

For example, do you know the probabilities of being born? How about one in four-hundred trillion? The probability of having chicken for dinner next Thursday? For that we’d need to employ the Total Probability Formula: p(A)=p(B)×p(A|B)+p(B)×p(A|B′), where A = having a chicken and B = having an opportunity to eat it.

People make all sorts of plans for a future that may never happen. Knowing this, we purchase all sorts of insurance against unfavorable outcomes. Whatever trajectory we hope we’re on, it’s impossible to calculate our destination with certainty; there are just too many unknown variables. We Buddhists view this situation in terms of collective Karma. Karma means action of both mind and body, and the effects of Karma span time and space. Actions taken in the past by people long dead still reverberate and influence our experience of the present; think Lincoln, Galileo, Mao, and Einstein (feel free to add your own to this list). Karma generates probabilities, and the intersectionality of collective Karma creates incalculable outcomes.

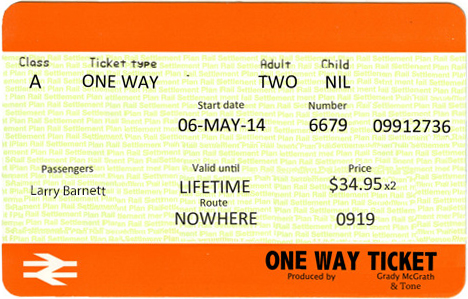

Simultaneously calculating the speed, position, and destination of a sub-atomic particle in the quantum realm is impossible; this is at the heart of Werner Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle. There are some things we just can’t know. So it is in our own material realm; none of us know how this adventure of ours will end. Well, that’s not exactly true. Tickets to our unknown destinations are one-way only. We’re all going to die; what we don’t know precisely is when, how and why.

A 65-year-old American male has a 35% chance of living until 90. Born in 1948, I have a 9.8% statistical chance of living until I’m 100, but of course we’re just talking in probabilities here. Statistical probabilities always deal in generalities and falter when applied to any individual life; in less mathematical terms, the Karmic forces are just too great for precise prediction, hence, the probable uncertainty of being.

I just love how you think, Larry! So very glad to have a ticket on this ride with you!