The word “privileged” is used to connote something akin to an honor bestowed upon a person due to their status or accomplishments, but today “privileged” is deployed as an insult. Ethnicity, gender, economic success, even age are now suspect, relegating matters of personal history, civic roles, social and family relationships to irrelevance. Being called “privileged” renders life’s particulars subordinate to the general.

In its own way, calling out privilege has become a method of stereotyping, a way to denigrate or dismiss others by invoking cultural or historical patterns to diminish the value of an individual. The idea of “male privilege,” for example, is based upon the general reality of male domination of society, not the particular behavior nor beliefs of an individual male. “White male privilege” adds a general, racially oriented historical context to the evaluation of an individual based upon skin color.

While there is value in exploring the effects of social history in one’s own life, seeing the ways in which society has been systematically structured to selectively provide advantages based upon general characteristics, when it comes down a particular individual’s life, generalities always fail to fully capture or express a complete reality. The use of phrases like “privileged old white man” assign demographically accurate but ultimately useless generalized stereotypes – classist, ageist, racist and gendered. Any evaluation of others purely based upon cultural stereotypes, no matter how they might be rooted in blemished social history, does harm when applied outside of the context of particulars.

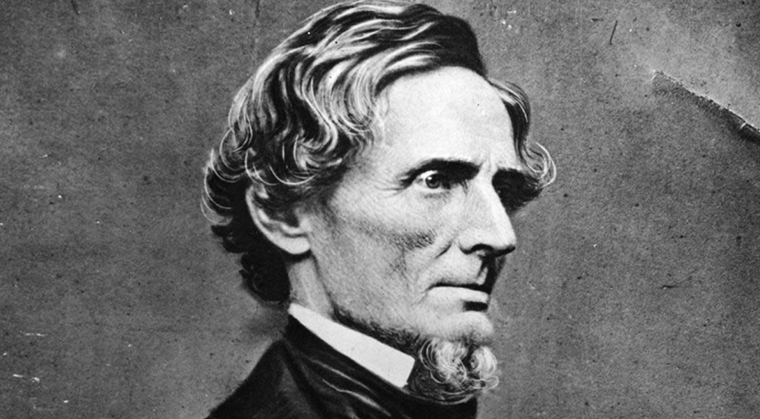

There is no doubt that to be born a white male in this society is to be advantaged, generally, over non-whites, but that advantage offers little if it occurs in a degraded context. Raised amid violence or abuse, whiteness bestows little privilege except when used as a foil to disparage, for example, blackness. In her book, Caste, Isabel Wilkerson explains how stereotyping elevates one group above another, no matter how socially degraded that “superior” group might be. Similarly, Ibrahm X. Kendi entitled his book on systemic racism in America, Stamped From the Beginning, a phrase used by southern senator (and later President of the Confederacy) Jefferson Davis in 1860 to assert why black-skinned people are, and would be forever, inferior to whites.

Conflating statistical or sociological generalities with the reality of particular lives of individuals serves to bolster caste distinctions, and when generalities become ideology, society suffers. Ideological purity is always dangerous. While it is true that all of us are embedded within social systems, the character and trajectory of individual lives is not entirely constrained by such systems. If that were the case, human society would be unchanged from its earliest forms. This is not to assert that history is irrelevant, but that the evaluation and understanding of individuals is incredibly complex.

Complexity demands intimacy, which is to say no individual life can be justly summarized by statistics or demographics. In order to know someone in all of their complexity, honest conversation needs to take place. Although intertwined, personal history is different than social history, and it’s unfair to conflate the two entirely. Accordingly, personal guilt can be distinguished from collective guilt; the beliefs and choices that individuals make have as much impact on society as demographics.

Stereotyping is always a shame agent, and shaming has become a dominant currency on social media. In childhood, we called it name-calling, and it still is.

larry: This gives me some clear distinctions to enjoy a more

useful discussions on these issues.

Thank you