When Sigmund Freud authored Civilization and Its Discontents in 1929, the world was in the throes of social, economic and political upheaval. The 1920s brought with it a post-WW1 era of explicit sexuality, financial excess then collapse, and world politics riven by domination, resistance and revolt. Seeking to understand why society appeared to be unraveling, Freud focused on the tension between individual freedom and the constraints placed on it by civilization, which he felt produced neurosis and unrest.

Today, nearly 100 years after Freud’s writing, we find ourselves yet again in the midst of upheaval. Gun violence in America grabs the daily headlines, tension between the world’s most powerful nations is ratcheting upwards, social and political movements are pushed to their extremes, immigration is fueling xenophobia, racial hatred and religious fundamentalism are on the rise, and the prolonged effects of consumerism and industrialization are seriously altering Earth’s climate. The rate of technological change is so rapid that human adjustment is nearly impossible. By comparison, Freud’s world was slow-paced.

As author John Zerzan points out, however, the social and psychological effects induced by civilization have always produced upheaval. In A People’s History of Civilization he concludes, “Since the Neolithic, there has been a steadily increasing dependence on technology, civilization’s material culture….One gets less than one puts in. This is the fraud of technoculture, and the hidden core of domestication: the growing impoverishment of self, society and the Earth.”

In making his case, Zerzan recounts constant and innumerable social uprisings over many centuries, particularly in response to the effects of industrialization and the ways it has disenfranchised and disorganized personal and family life. He does not address the effects of surveillance capitalism, the ultimate reduction of human beings into what writer Michel Foucault called “calculable units,” but he makes his point.

Humanity, always prone to a retreat into the symbolic, has progressively lost touch with what’s real, namely the ground beneath our feet and the living world that springs from it. When, as psychiatrist Jacques Lacan suggested, imagination is added to the mix, humanity becomes even more alienated from the real. Freud speculated that religion developed in response to the stress of civilization, but religious-like symbolism and imagination permeate the entirety of human life. An example is economics, where the value of world currencies exists solely in the imagination. The rise of digital currencies like BitCoin is illustrative.

Currency was once comprised of precious metals, gold and silver coins. Not simply tokens or symbols of wealth, such metals could be melted and reworked into myriad forms. Replacement by paper money required faith, faith that symbolic paper currency could be exchanged for precious metal, but once the gold-standard was eliminated, faith in precious metal was replaced by faith in the imaginary. That faith is now placed in electronically stored “data” representing accumulated wealth, digital bits existing in cyberspace. BitCoin is simply a new article of faith with no basis in anything real except common agreement that it exists and can be exchanged for goods and services.

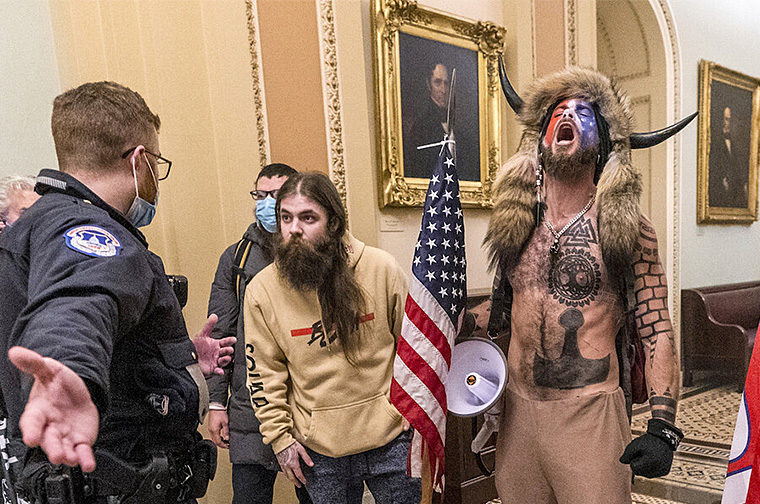

Our separation from the real leaves us in a dream world of our own making, one filled with hope and fear but bereft of much in the way of exercising direct influence; little wonder that paranoia, conspiracy theories, confusion and mental illness develop. As the Capitol riot of January 6th demonstrates, civilization produces malcontents. And it always has.

Faith in any currency, whether it be Bitcoin or fiat, is not really faith in the “imaginary.” The ability to exchange any particle of metal, paper or digital sequencing for goods and services—food, shelter, education, transportation, entertainment, bribes, etc.—is arguably not imaginary. It reminds me of the question I have asked every dharma teacher and for which I have never gotten a definitive—or even satisfactory—answer: If there is no self, no “me,” then who pays the rent? You can imagine whatever sort of world or or philosophy you like, but when the rent comes due, somebody gotta pay up. That is not imaginary. Its as “real” as we get around here!

Cheers!

Hi Tom: The paper or metal clearly is real, but the value it represents occupies the imaginary sector of human thought. If human beings disappear, the value disappears, even if the paper or metal remains. That we are capable of inhabiting an imaginary economy provides an illusion of real, but if the stock market crashes or inflation skyrockets, it provides a demonstration of just how imaginary the value of currency can be. That the landlord is willing to accept a check gives testimony to the power or convention, not, I think, the reality of the value of money. It is tantamount to real, and that’s how we treat the value of currency, but it’s just an idea that everyone accepts. Have you read “Debt” by Peter Graeber? I highly recommend it.