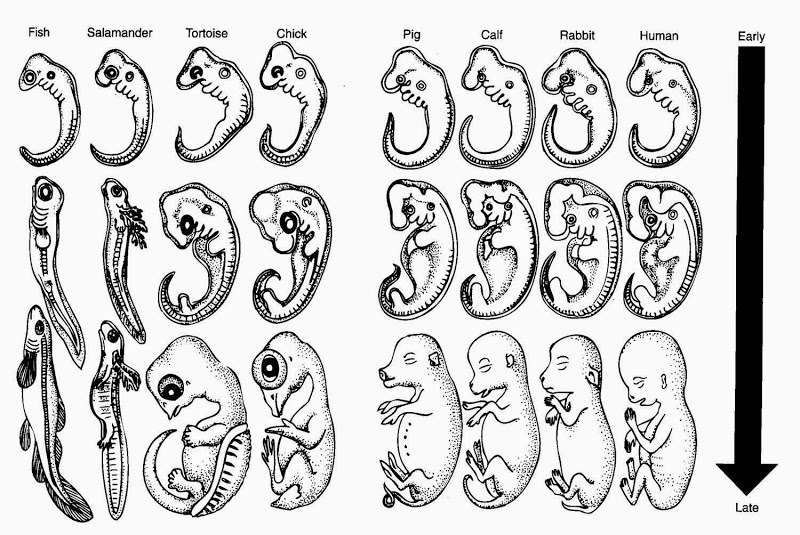

I recall my high school biology teacher, Mr. Ricci, explaining the phrase “Ontology Recapitulates Phylogeny”, as much because his long, snagged teeth made saying it nearly impossible for him to say, an amusing moment for us sophomores, as for the sheer poetry of its sound. It’s meaning — that as a fetus develops it physically displays its evolutionary genetic path — was made memorable by slides of human embryos varyingly displaying decidedly inhuman features such as proto-gills and tails. Embedded within the human genome is the history of animal life on earth.

It’s not mere history, however. Our physical selves have evolved, but various pre-human features remain embedded deeply within and under layers of accumulated change. This is true, particularly, of the human brain, which retains primordial structures and neural networks buried under masses of evolutionarily acquired nerve tissues such as the cerebellum and cerebral cortex. The “reptile brain,” in this sense, literally refers to the oldest brain structures organized with archaic threat and aggression networks vital to survival of any animal organism and still active in everyday human life.

So, too, the “mammalian brain” is at work, stimulating bonding hormones like Oxytocin that operate on the emotional centers of the brain, making matters of trust and security central to our human lives. While birds and some reptiles often protect and feed their young for a short while, mammals experience relatively long periods of dependence and human beings have the longest period of child-rearing dependence of all mammals, by far.

Thus, socially, we witness the manifestation of our genetic inheritance in observing the ways we treat and mis-treat each other, partially due to the over-sized influence of one part of the brain — like the reptile part — or another. Add to this matter of genetics both epi-genetics, the influence of environment and experience on living things, and the vagaries of chance. Epi-genetic “memory” — the effect of experiences such as severe hunger, physical abuse, feeling loved — is transferred from parent to child and to successive generations just as surely as physical genes themselves, inhibiting and exciting gene expression, ie: turning genes “on” or “off.” How we raise our children resonates through future family history.

Chance, spontaneous genetic mutation, may account for the ascent of Homo sapiens altogether. Current human genome studies indicate the inclusion of many more “junk” genes than previously predicted. Embedded in each of us is not only the genetic history of all animals, but non-animal life as well such as viruses. Our cellular mitochondria — the organelles within each living cell that are essential in supplying energy — appear to have been shanghaied by primitive animal life from bacteria, and contain their own DNA. In short, people are a genetic melting pot, largely erasing the validity of hard boundaries and distinctions human society outwardly prefers.

We are not as autonomously human as we suppose. And the implications? Chill, people. Yes, the world can be threatening and dangerous, and five hundred years ago being killed by a wild animal was a legitimate threat. Today our greatest threats reside in our imagination and the ways in which it stimulates our primitive reptile brains. Better we rely upon our mammalian brain, upon confidence in trust and security, and our capacities for reason, understanding and empathy. For to fall prey to fear-based reptilian patterns of behavior, from an evolutionary standpoint, is tantamount to moving backwards.

Makes me wonder. Do I have lots more of that “primitive” animal brain than others? Even the reptiles? Maybe that is why I stopped eating and wearing them. This includes letting the bugs etc. just live on the property. I love what you have written, but just because they came before us, do we know how they think and feel?