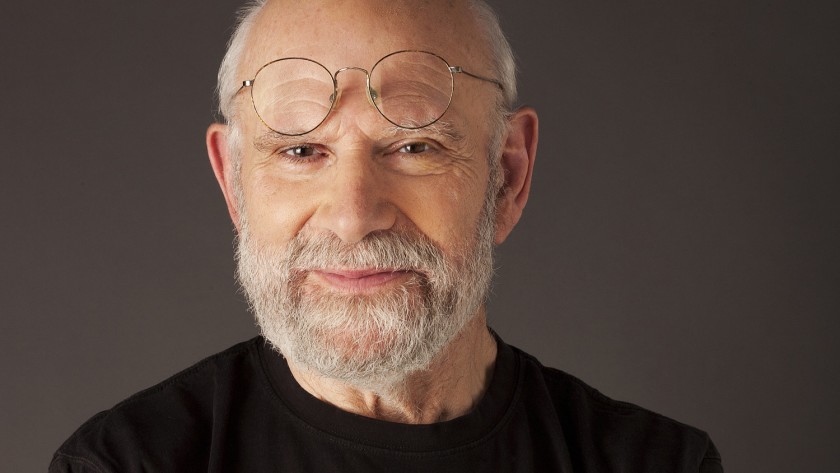

Oliver Sacks, the best-selling author/neurologist, has died. In his inimitable style he wrote about his impending death from metastatic cancer in articles in the NY Times, and as it true of all his writing, his keen observation and fondness for humanity jumps right off the page.

My first exposure to Oliver Sacks did not come from reading his popular books, but from working on the design of the cover of his first. Entitled “Migraine: History of a Disorder” it was published by U.C. Press in Berkeley, the publishing arm of the University. It was a short, rather scientific book, quite dry and academic, as were most of the U.C. Press books at the time. For the cover we used a drawing of a face by the then five-year-old son of a friend, a typically wild and expressive child-like drawing in black crayon. In place of the original black eyes, we placed two bright circles of red. We thought it worked, and so did U.C. Press.

Later on I read Sacks’ “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat”, a book recounting various strange and serious neurological disorders of his patients. The man of the title, for example, had lost the ability to distinguish the purpose of objects; he reached for his wife to greet her, but then attempted to place her on his head. Another patient could perfectly describe a glove he was looking at in great detail, but could not say what it was or what it was for. The stories were intriguing, but more intriguing was the way Oliver Sacks would find the way to touch the heart of each of his patients, despite their terrible neurological difficulties. In this way he displayed his great love of humanity, and revealed his own.

Sacks went on to write and publish an impressive number of books, some about his work as a neurologist and others about his own life and his own particular interests. A bit of a poly-math, those interests ranged from music to exotic plants, neuroscience to chemistry, swimming to travel. No matter the subject his literary voice sang of richness, possibility, human decency, and compassion. When he finally wrote about his own homosexuality, about which he had harbored feelings of guilt and shame, the last of his personal veils was lifted. Not long after, his diagnosis of metastatic cancer was made.

I’ve always preferred non-fiction to fiction. It’s not that fiction isn’t powerful and affecting, but given limited time I’d rather read books that I call “faction”. Oliver Sacks’ books contain all the mystery and enchantment found in books of fiction, but contained within reflections of what it means to be human, even when that experience is constrained by severe cognitive constraints due to illness or disease. His work explores the source and emanation of dignity even in those individuals who cannot communicate with words.

He has been writing about his own impending death, and now it has come; his formerly robust physical self strengthened by years of swimming disappeared. He was observing and documenting his own demise with a tenderness and gentility he has previously reserved for his patients. Now gone, we have lost a true humanitarian, a man who found his voice by giving a voice to the voiceless. It is a priceless legacy and one that I will appreciate always.