Europe has a lengthy history of philosophical thought, ranging from ancient Greeks such as Aristotle up to and including English, French and German philosophers of the 20th Century. Knowing and the nature of knowing have occupied some of the greatest minds in Western culture.

On the Asian continent, including India, China and Tibet, such speculation also abounds, and its history extends back well before the Greeks. Mind, consciousness, self, non-self, knowledge and wisdom, among other areas of inquiry, fill uncountable ancient manuscripts as well as modern commentaries by the brightest minds of each period.

I’m currently spending a week with six others interested in such matters, talking about conventional beliefs about reality and ideas pertaining to less conventional and more subtle speculations. Our five hours of daily discussion are led by Jules Levinson, Phd., a distinguished translator of Tibetan who has studied with great teachers and Lamas in India, Nepal and here in America for 35 years.

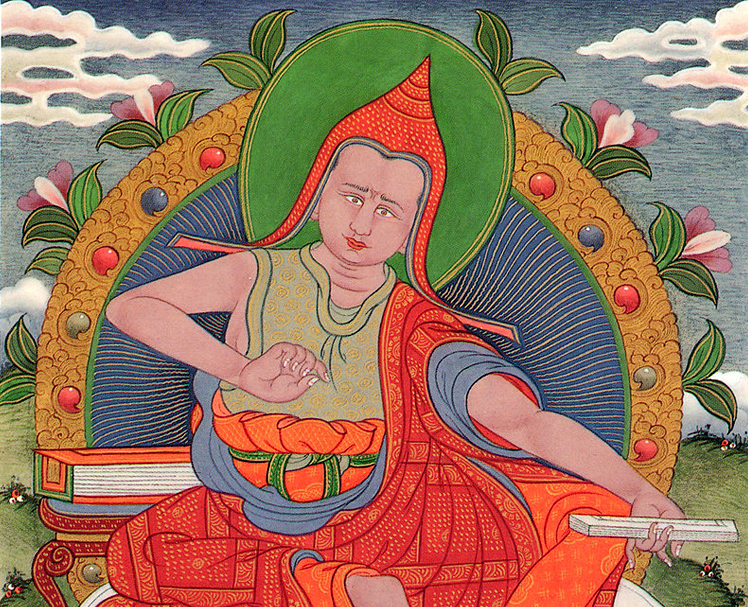

We spent five hours discussing a four-line stanza of a 7th Century work by the famed Indian scholar Chandrakirti. Consisting of no more than perhaps 30 words, we looked at each word and phrase from every possible direction; the meaning of the original words and how they translate into English, the various translated meanings and idioms, how the words relate to knowledge, history and Buddhist practice, and our own personal associations with the words.

It’s hard to find people to talk to about such heady stuff; I’ve tried. Some complain that talking about such things makes their head hurt. Others tell me they have no interest in these sorts of topics at all. The long and short of it is that discussing the nature of reality is to most people a terrible bore. To me it’s as much fun as being a pig in big puddle of mud.

The point of such inquiry is not the inquiry itself; rather it is what emerges out of the inquiry. It’s not a matter of exhausting conceptual mind, though some have suggested to me that my obsession is about just that. It’s not about being right or wrong and coming to such conclusions, though it’s always interesting to discover how completely clueless I am. No, these discussions are about opening up the mind by pondering the imponderable, prying apart the usual container of beliefs that confine thought and emotions within their typical comfort zones. Having done that, the experience informs contemplation and meditation, deepening understanding and reducing confusion. In time, it is said, wisdom may emerge!

In the text we’re studying, the argument is made that the true nature of reality cannot be affirmed or even described. Words, which are symbolic mental representations of objects or concepts, cannot by their nature convey the ineffable, which is beyond description. However, words can be used to negate affirmations about reality, using logic to collapse any such attempt to define the ultimate nature of things. While some might view the result as nihilistic, it is said that having proved that nothing can be affirmed about ultimate reality – when all is negated – what is left to know is the ineffable. This experience cannot be expressed, but can be realized.

So it is we talk, listen, study and ponder, all of it in service to the goal of no more learning.