Belief is a choice, and human belief systems vary widely. Presently, belief in scientific rationalism is dominant in developed societies but this choice is culturally determined and not universally accepted. History and the imperatives of religious belief continue to challenge the materialism of scientific rationality, resulting in cultural struggle, or what writer Max Weber, author of The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism (1904), associated with kulturkamph, the 19th century struggle in Germany between Catholicism and Protestantism. Notably, in 1992, Republican Patrick Buchanan, columnist, former speech writer for Richard Nixon and Reform Party presidential candidate in 2000, characterized the conflict in America as a “culture war.”

America’s kulturkamph, like all cultural struggles, is a combination of competing belief systems supported in varying degrees by education, peer pressure, religious doctrine and power structures. Education in one sense is propaganda, insofar as it is indoctrination into a culture’s dominant beliefs, including the belief that universal education itself is important. The latter rationale was championed by China in 1950 when it invaded Tibet, which the Chinese considered mired in primitive religious belief and institutions. That same rationale is offered by China today in justifying its internment of millions of Uighur Muslims for reeducation.

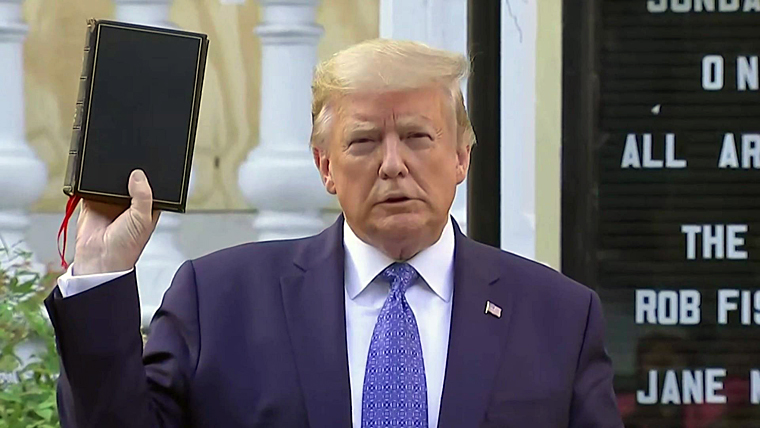

In our schools, kulturkamph fuels conflict about which textbooks to use, what to teach, and whether or not to allow prayer. Prayer is anything but scientifically rational, yet remains a prominent fixture of American life; congressional sessions begin with religious invocation and prayer. The struggle between cultural beliefs dominates every governmental policy discussion, and fixtures of scientific rationalism and religious doctrine are used as props to gain political traction and power; Trump’s photo-op holding a bible in front of St. John’s church was propagandistic use of a sacred symbol for political purpose, an act of profanation.

When the Spaniards invaded Mexico in 1519, they were shocked to discover towers of skulls amassed by the Aztecs, the product of an industrial-scale religious system of human sacrifice. That the Spaniards, infamous for their savagery, were shocked is ironic, but the cruelty of their Catholic faith was based upon a different belief system than that of the Aztecs. In Aztec culture, to be selected for sacrifice from among the Aztec population was an honor, and such sacrificial victims were feted, pampered and treated lovingly in the period before their death. In contrast, the Catholic inquisition viciously tortured its victims before death, burned suspected witches and heretics. Protestant settlers in America hanged suspected witches, based upon Puritan belief in the supernatural.

Present day cultural struggle in America has religious underpinnings akin to Germany’s kulturkamph. The late Congressman John Lewis was a deeply religious black man whose Christian faith guided his non-violent civil disobedience, yet his actions were in the face of violence by equally religious white Christians. Currently, the struggle between scientific rationalism and religious faith has become increasingly visible due to the pandemic; for some, the wearing of a facial mask is tantamount to political profanation.

The regrettable product of post-modernist thought – that all truth is relative – legitimizesevery belief system, exacerbating America’s kulturkamph. When willful ignorance is added, it creates an even more complex and difficult situation. Trump’s willful embrace of magical thinking, like injecting disinfectant and that the coronavirus will just disappear, is the antithesis of scientific rationalism. In theory, democracy is intended to mediate kulturkamph, but that, ironically, requires confidant belief in democracy itself.