The past 500 years of social change can be summarized in one word: emancipation. Despite the repeated pendulum swings of permissive and repressive governments, religions, and politics, the overall trajectory of history, in particular western history, includes greater freedom for more people, not less.

There are, of course, places in the world where freedom is considered dangerous, that it promotes wildness and decreases order; the People’s Republic of China comes to mind. In such places the full apparatus and instrumentality of state power are used to suppress freedom. Clearly, whether or not freedom is the natural state of humanity remains a matter of opinion, but the very fact of its active suppression by law or edict indicates that it is.

Even in the west, for those still struggling to overcome repression at the hands of others, a history 500 years of emancipation gives cold comfort. The universal ideal of freedom is of little significance to those who remain stuck at the bottom of the social and economic ladder due to systemic bigotry, racism, and patterns of generational poverty; it is life lived here and now that matters most for them, and ultimately, for all of us.

This raises the fact that we each simultaneously inhabit two roles: the particular, subjective role of living here and now, and the general, objective role of occupying a place in history. Here and now is always particularly subjective; self-consciousness demands it by observing itself as one entity existing among others. The subjective self objectifies others and remarkably, can even objectify itself.

Our place in history occupies that of a generally objective fact: instead of being here and now, we are who and when: name, date, ancestors, occupation, and so forth. Objectively speaking, we each are a statistic. Thus reduced to a calculable unit, we each assume a place in the history of our species, one counted among many billions.

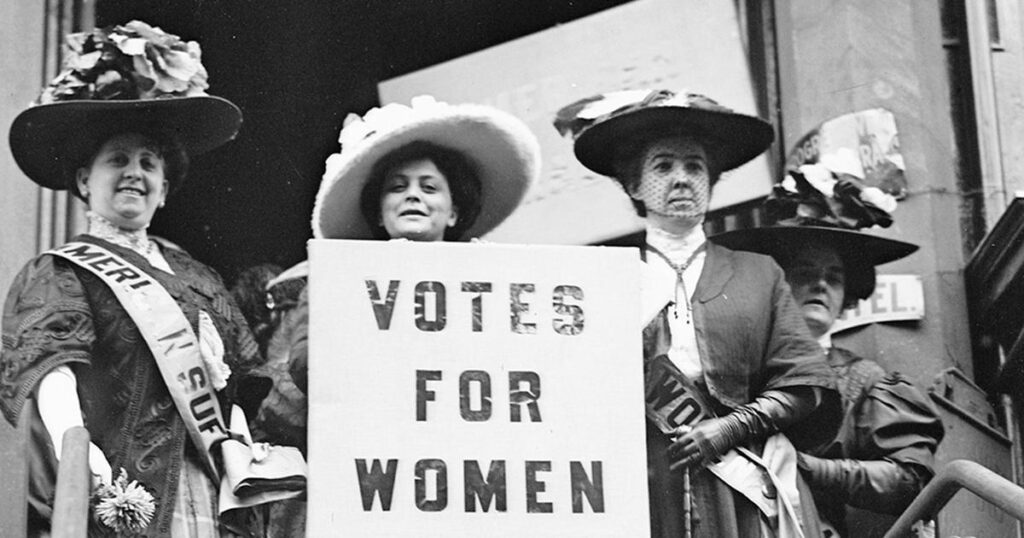

Right now, as it always has been, America is in the midst of a vigorous debate about freedom, who should have it and to what degree. The emphasis of the last 250 years in America has been an inexorable, albeit terribly slow, granting of freedom to an ever-widening spectrum of people. Ethnicity, economic status, gender, national origin; all of these have have been criteria at one time or another.

The spirit of emancipation spreads by example; “If you are free, why not I?” Logic demands an answer. Objections, however, are often irrational, ranging from “you’ve not earned it” to “you’re not a real American.” While our freedom is regulated by law and social convention, if indeed freedom is our natural state the denial of freedom’s a tough argument to make, and even tougher to pull off. To do so sometimes require the use of brute force, violence, and incarceration.

The forces opposed to freedom are gaining strength, not just here but in other western countries; like freedom oppression too spreads by example. Despite history’s ample and often horrid examples of tyranny, humankind seems doomed to repeat its past mistakes.

Being here and now is so compelling, and ultimately so demanding, that caring about our role in history tends to pale by comparison. First and foremost, our instinct is to survive, and that means filling bellies, staying warm, and having a place to live. Preserving freedom also requires constant effort, however; not only for oneself, but on behalf of everyone else.