Our planet’s major religion is a materialist ideology that’s quickly bringing civilization to its ultimate crisis: consumerism. Having transformed humankind into Homo economicus, consumerism has invaded and replaced virtually all indigenous cultures, producing a homogeneous world civilization based on accumulation of wealth.

Although we think of wealth in terms of the super-rich like Jeff Bezos or Bill Gates, in its simplest form wealth is the accumulation of surplus, possessing more than is needed to sustain ordinary life. Wealth began as a by-product of Neolithic agriculture; abandonment of the Paleolithic, nomadic lifestyle of foraging and hunting in favor of fixed agricultural settlements requires hoarding. That shift created cities, their construction and defense, private property, farm labor, accounting and criminality. In A People’s History of Civilization, writer John Zerzan writes that the record of the past 10,000 years is one of aggressive patriarchy pillaging Mother Earth.

If poet/author Robert Graves is correct, Greek mythology points to prehistory: the tale of Hermes’ theft of Apollo’s cattle, for example. Hermes, the personification of wit and wile, the singer of songs and guide to the underworld of human consciousness, decides to steal Apollo’s herd and hide them. Apollo, personification of prophesy, ritual and order, furiously searches for his cattle, but in the end must negotiate with Hermes and grant him legitimacy in exchange for the return of his possessions. The cattle are returned in exchange for Hermes’ enchanting songs, what today we hear as the jingles of advertising. Mythologically, the trickery of Hermes and the ritual order of Apollo shared leading roles in human culture, and so it remains to this day; it’s on TV.

People have mixed feelings about television, but I watch it with an appreciation of its mythological roots. It’s possible to become absorbed in its exciting or romantic narratives, of course, but that’s just at the surface. At a deeper level, the partnership-rivalry of Hermes and Apollo continues, generating a meta-narrative about accumulating wealth, trickery and deception. The materialist Apollo promotes ritualistic accumulation, what we call wealth, while the trickster thief Hermes uses wit to cleverly swindle it, what we call advertising.

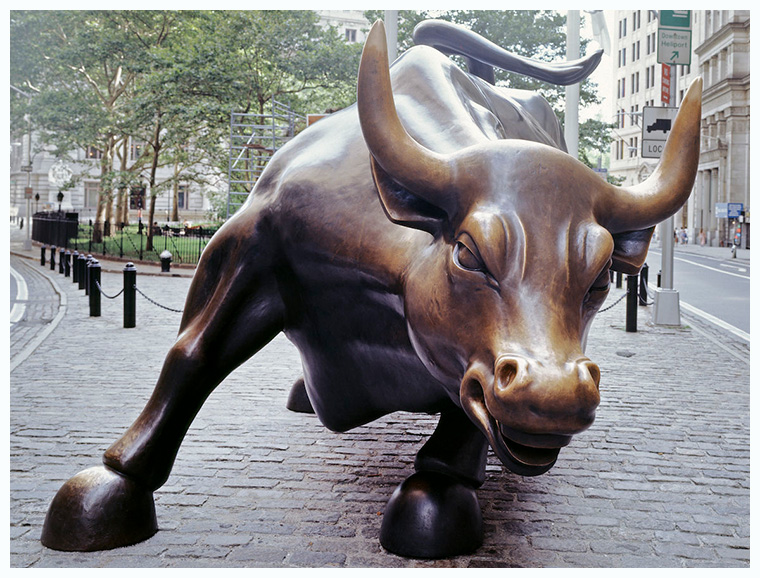

Advertising is about stimulating desire to promote consumption that depletes accumulated surplus. Given the plethora of burger commercials on television – think of the classic “Where’s the Beef?” slogan – it’s ironic that Greek mythology about private property and theft begins with cattle. But accumulated surplus, what philosopher Georges Bataille called “the accursed share,” now extends to everything. By today’s standards, one can never have enough – not enough stuff or money and not enough insurance against the loss of either. Caught tightly in a grip between Apollo and Hermes – accumulation and the trickery of debt – civilization is suffocating under the squeeze of economy, a powerfully inhuman master. And when nations acquire a surplus, it’s used wastefully, billions spent on warfare, developing nuclear weapons and producing distracting entertainment; this, while entire populations go hungry.

Despite the treasure poured into it to make it seductive and entertaining, advertising is so intrusive, pervasive and distasteful that it even rejects itself. Hermes as liar and a thief empowers content-streaming services like HBOMax, Disney and Netflix to proudly advertise themselves as “commercial free.” Subscribers now spend their surplus money to avoid commercials intended to induce them to spend their surplus money. In the end, Hermes once again tricks us in order to steal our cattle.

This reminds me of two related comments I have heard. One recently from Fran Lebowitz: There are two kinds of people in the world; those who think there is such a thing as enough money, and people with money.

The other is from Dr. Uemura, my philosophy prof decades ago. In speaking about Plato’s notorious exiling of poets from his ideal society, he defended the notion by pointing out that, in classical Athens, poets were, in effect, advertisers, hired by politicians and other interests to influence the public. If you have poetic talent and want to make some real money, your options are 1)popular song lyrics, 2) political rhetoric and 3) advertising.