In mapping brain function, specific areas of the brain have been found to be primarily responsible for particular functions, such as hearing, seeing, feeling, motor coordination, reasoning and so on. Despite this clustering of functional areas, the brain is nonetheless capable of fully integrating input between varying brain locations and producing an uninterrupted and generally functional sense of self and reality. Neuroscientists estimate that the billions of neurons in the human brain establish hundreds of trillions of connections with each other.

The periods of life during which many of these connections are created are infancy and toddlerhood. I’ve watched this happening as our granddaughter Isabelle, now nine months old, has become intensely curious about everything within reach. She does not understand the world well, but she clearly senses that something is happening, and she wants to know about it. Her brain is furiously constructing what neuroscientists call brain/body maps, mental configurations of one’s body and the world around us.

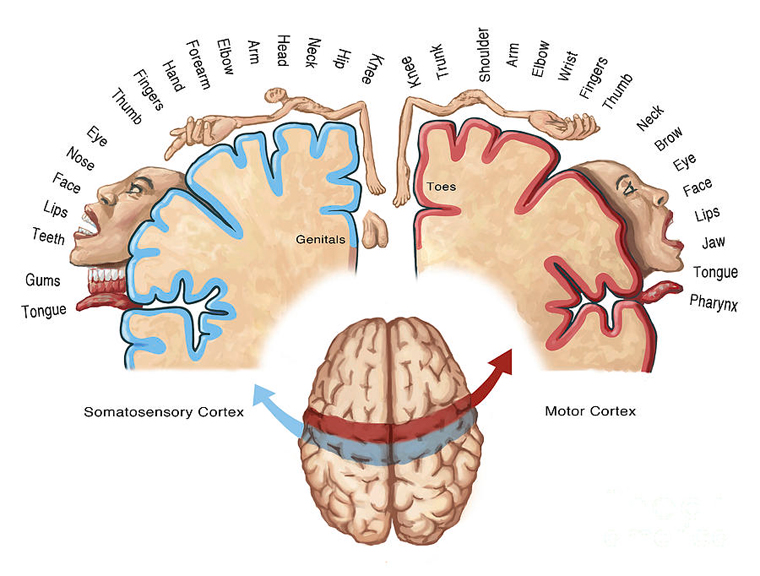

Brain/body maps allow us to move and function properly in the world. Within our minds the postural arrangement and functioning of the body’s movements are replicated in a network of neural connections activated when we move and also when we are just anticipating movement. Just as various areas of the brain become activated when we dream, and readings taken of the brain reveal optical or hearing centers activated when we dream of sights and sounds, so when we are awake and anticipate or imagine movement, areas of the brain/body map are activated.

For example, in thinking about playing tennis – visualizing the swing of the racket and hitting the ball over the net – the centers of the brain responsible for those movements are activated in precisely the same way as when those movements are physically performed. Moreover, studies of brain/body maps shows that individuals can markedly improve their physical performance simply by visualizing a specific physical activity for regular periods over time. Remarkably, the degree of improvement closely matches that of those who engage in physical practice. This is as true in playing the piano as it is in tennis, golf or hitting a baseball. These findings have changed the nature of sports and musical training, as well as methods of rehabilitation for head trauma, physical injuries or stroke.

The implications of mental training for the development of new brain/body map connections are intriguing when considering other human behaviors. People engage in many activities that have a physical component, but also include emotional and sensate qualities. Material generosity, for example, involves attitude, emotional feelings, and the actual physical act of giving. If the mental activation of brain/body maps can improve playing the piano, can a similar activation improve generosity? Does the imaginary exercise of generosity – visualizing the transfer of an object of value to another person and forming feelings of openness and kindness towards others – actually lead to an improved capacity for giving?

The brain/body map is created over time, and our ability to adapt to changing conditions is a reflection of our ability to alter the brain/body maps within us. Studies prove that this ability lasts a lifetime, which means it is never too late to learn new things or change our ways of being. Practice it seems – be it physical or mental – does indeed make perfect.