Historians call this current age “modernity;” its defining characteristic is rapid change. Modernity began in earnest with the industrial revolution. When machines replaced man as the primary means of production, the technological age of modernity began to rapidly transform ways of life that had been in place for millennia. From agriculture to information, everything about modernity pulls the rug out from underneath society and culture. It sets us off-balance and generates social, political and cultural transformation, sometimes for better, sometimes for worse. Modernity’s rate of change has never been faster than it is today.

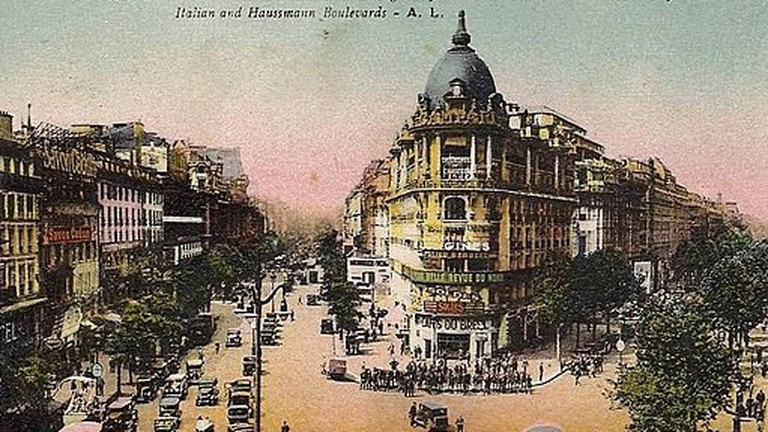

In the 19th Century, modernity transformed the ancient French city of Paris into the marvel of grand architecture, broad vistas, and wide boulevards that attract tourists from around the globe. When Baron Haussmann, the architect and city planner who transformed Paris in the mid-1800s implemented his “modernization” plan, many 500-year-old neighborhood villages were entirely demolished in the name of “progress.” This resulted in the “old” Paris that we modern people adore, and also complain about as it continues to change.

So it is with Sonoma, which continues to change. The tension between private property rights and community rights always generates friction, as Prop. 90, narrowly defeated in this past election, amply demonstrates. Modernity is also about the “force of law,” and its extension into virtually every nook and cranny of modern life. When it comes to land use, government cannot simply tell others what they may and may not do outside the force of law. And in modernity, the force of law is also about the force of money. It is impossible to separate the discussion of land use and development from the subject of money, investment and desire for profit.

Ironically, historic preservation is a by-product of modernity. If things did not change so quickly and so often, preserving the past might be of less concern; for much of history, it was not. For example, during the 1960s a gas station was proposed and seriously considered for construction in a western quadrant of the Sonoma Plaza Park.

There are some in this community who would like to go back to a simpler time with simpler values. Such feelings are entirely understandable. To those who lived here before traffic lights and SUVs, before gangs and graffiti, big budgets and government mandates, memories of “old” Sonoma must feel like fading dreams. Yet, memory is a funny thing; we pick and choose what to remember. And history is a thing remembered, too, selectively chosen from the record of events. To be sure, life in the past was not all daisies and roses. There was sickness, old age and death, poverty and pollution, but these are not the things that most choose to remember. Most recall the pleasant things, the sweet moments that made life good.

Modernity and all that it brings with it insures that things will change. We should plan for it, regulate it, monitor it, anticipate it and cope with it the best we can. We cannot stop it. Time moves only forwards, never back. The world does not stop, and we can’t get off until we die. And even then, as they say, life goes on.