Sitting here in the “land of the free” while much of the world struggles with democracy and reorganizing society, I can’t help but contemplate the meaning of freedom. Tossed around liberally by conservatives, freedom as a word seems to have morphed into a convenient catch-all political platform.

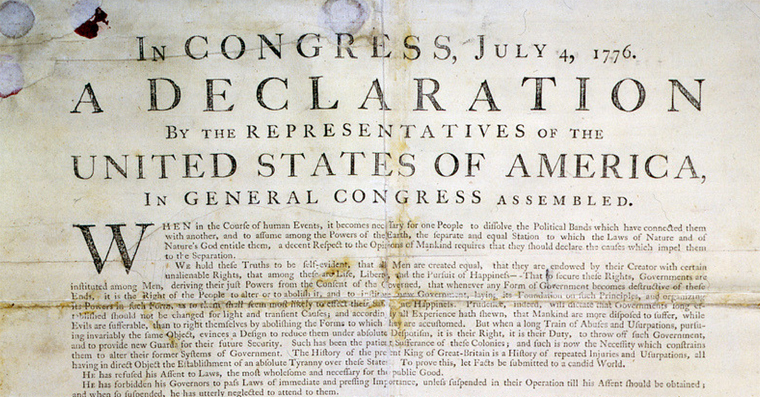

But what of freedom; is it something granted or a birthright? Political thinkers in Europe’s Age of Enlightenment, from whom America’s founding fathers borrowed phrases and richly endowed our Declaration of Independence without attribution, considered freedom a birthright of Natural Law. Thus the phrase “all men are created equal” (appropriated from British philosopher Thomas Locke’s Second Treatise of Government written in 1690), applies precepts of Natural Law to birth. It’s worth noting Locke and our founding fathers also considered Natural Law justification for slavery and the second-class status of women, viewed as the “lesser sex.”

Today’s Libertarians and conservatives gravitate to Natural Law precepts, and their acceptance of legitimate government goes only so far as the idea that government’s paramount role is to protect private property. That this opinion is vintage 17th Century philosophy about civic society makes it all the more sacrosanct; the Tea Party name is entirely apropos. Ironically, the freedom to own begets the freedom to shop, which gives rise to the freedom to sell. Thus we find ourselves stuck in the mire of a relentless modern day materialist free-for-all. But wait…there’s more!

In commercial terms, free means getting “sumpin’ for nuttin’,” an infallibly faithful sales technique despite common knowledge that no “free lunch” is “free.” We also employ phrases such as fragrance-free, carbon-free, aerosol-free and the like, all of which use free as an indication of absence. In the meantime, freedom from want, freedom of expression, freedom of religion and a variety of other freedoms are now part of our everyday national narrative. In short, we are so free in the use of the word free it’s no longer terribly meaningful.

Whether all of us are naturally “born free” remains an interesting area of inquiry. Despite the conventionally popular view, we do not emerge from the womb as independent full-fledged citizens; to the contrary, we are born totally helpless, completely dependent, and then spend many years in childhood accommodating ourselves to a well-established system created well before our arrival. This system is a collectively held set of cultural norms, symbolic meanings, proscribed behaviors, established views and popular attitudes; none of us are free from all that, ever. Thus freedom, even the freedom of Natural Law, is never absolute. We cannot as individuals be separated from society; we explore freedom in relative terms only, political opinions notwithstanding.

French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, never one to be afraid of controversy, opined that the freest among us are psychotics. Unbridled from the common cultural norms or other customary restraints of society, psychotics explore spaces most of us cannot or choose not to access. That such psychosis can fuel the creativity of an artist, such as Vincent Van Gogh, is without dispute. Of course, his creativity also came at the price of cutting off his own ear, which he was free to do, as are we all. Perhaps ear piercing is a symbolic nod to the freedom of our own latent psychosis.

Ultimately, freedom is just another word. What it means is up to each of us.